The Drama

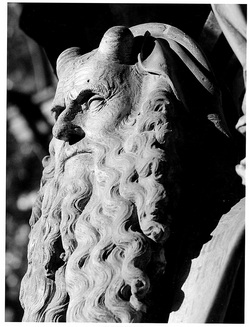

Figure 1. Morand, Kathleen. Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

April Czarnetzki

One word comes to mind when a modern day viewer first experiences Claus Sluter’s Well of Moses: drama. The Well of Moses which once stood at about 24 ½ feet tall was always meant for drama, even in the days of its seclusion in a monastery in the Chartruese de Champmol. Claus Sluter's Well of Moses was an integral piece that influenced the Northern Renaissance's shift from stylized figures towards realistically, dramatically, and individually depicted figures in sculpture in the beginning of the 15th century Germany. This shift in depiction was vital to the expansion and assistance in modern devotion of this time. By portraying figures in such a manner, the stone becomes flesh and their life-like qualities have an affect on the viewer by assisting in reaching a mystical and intimate devotion by making their faith life real, present, and demanding of their attention.1 Sluter himself joined a monastery the same year that the Well of Moses was completed, which further connects the affect that the detailed emotions shown in the piece can create for a viewer.2

The figures depicted in the Well of Moses are Christ Jesus, and the Old Testament Prophets: Moses, David, Jeremiah, Zechariah, Daniel and Isaiah. Sluter displayed these life-size figures in a hexagonal manner so as to guide the viewer all the way around the sculpture to make eye contact with the figures on every side.3 Sluter chose this arrangement purposefully in order to move the viewer around the piece visually and direct the attention of the viewer towards their faith through the majestic and dominating presence of Christ and his prophets.4 The upper portion of the sculpture once contained a Calvary scene with Christ on the Cross, the Virgin Mary, St. John, and Mary Magdalene, but now only fragments of Christ’s torso remain. Sluter portrayed Christ in a way that viewers would look up into his face and experience empathy.

Today the drama is still felt but has perhaps lost some of the emotion that early 15th century viewers would have experienced from the presence of the Great Cross atop the fountain. The crucifixion scene was the focus back in the creation of the fountain, guiding viewers to feel empathy and repentance of their sins when looking to the Savior’s sacrificed body. If their gaze broke from the cross, their eyes were met with the life-size prophets pointing to inscriptions of their visions foretold. With these expressions of ferocity, animation, passion, and intimidation, viewers were surely assisted in having a spiritual experience. Today, the cross is no longer attached to the fountain but the forceful presence of the prophets remains.

The importance of each of the prophets can be explained by the way that they are sculpted and the inscriptions and symbols they carry. Researchers have discovered that the orientation of the Well was with Christ’s body facing East.5 With this information we find that David is directly beneath where the cross was originally placed. This careful positioning goes along with David being recognized as falling in lineage with Christ. Moses carries the Tables of the Law, or the Ten Commandments, the Law of God which was sent to Moses to share with the world, as well as displaying horns which were typical of medieval depictions to represent rays of light (Fig. 1).6 In Jesus’ life he preached the Tables of the Law in his Sermon on the Mount. By dying on the cross in fulfillment of the Old Law with a promise of a New Covenant was foretold by Jeremiah and accomplished by Christ. The figures all hold their prophecies and each have their heads turned in a manner that helps the viewer circulate around the fountain. Each of the prophets has an individualized face ripe with emotion shown through details on their faces by furrowed brows, fierce gazes, vulnerability, scruffy beards, and billowing garments, that despite their animation, fall naturally and realistically as though a living human body was beneath.

The drama of Sluter’s sculpture was inspired by the sacred theaters of the time.7 Because the general public did not have access to the Bible, liturgical dramas were common for telling the stories of the Bible and sharing moralities. The grand scale of the sculpture and costumes worn by Sluter’s prophets furthers this concept that his sculpture was a stagnant version of the religious theatricals of his day. Because of the plays, people were familiar with the prophets and the roles that they played making them easily recognizable. This is another link in how the drama inspired by the plays and instilled into the Well of Moses figures has influenced personal devotion in the 15th century.

Sluter himself must have been moved in his own faith through the creation of his sculpture because he joined a monastery towards the completion of the Well. The drama of these figures certainly assisted viewers in mystical visions and personal devotion because of the overwhelming power and emotion from the intense gaze of the prophets that evoke discipline, Christ's expression of pain that evokes empathy, and even from the angels wrought with grief for their crucified Lord as they wipe the tears from their eyes.8 The Well of Moses was able to convey the emotions of an oil painting by expanding the constrictions of a frame and making the figures come to life, setting the bar higher for the expections of 15th century German sculptures in their assistance in personal devotion.

Works Consulted

Freedberg, David. "Claus Sluter's Mourners." ARTNews 94, no. 1 (1995): 119-121.

Kuhn, Charles Louis. German and Netherlandish Sculpture, 1280-1800. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Pr., 1965.

Morand, Kathleen. Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

Müller, Theodor. Sculpture in the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Spain: 1400 to 1500;. Baltimore: Penguin, 1966.

Nash, Susie . "Claus Sluter's 'Well of Moses' for the Chartreuse de Champmol Reconsidered: Part 1." The Burlington Magazine 147 (2005): 798-809.

Endnotes

1 Freedberg, "Claus Sluter's Mourners." 119

2 Morand, Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy.

3 Nash, "Claus Sluter's 'Well of Moses' for the Chartreuse de Champmol Reconsidered: Part 1." 798

4 Müller, Sculpture in the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Spain: 1400 to 1500. 11

5 Morand, Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. 101

6 Morand, Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. 97

7 Morand, Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. 103

8 Freedberg, "Claus Sluter's Mourners." 119

One word comes to mind when a modern day viewer first experiences Claus Sluter’s Well of Moses: drama. The Well of Moses which once stood at about 24 ½ feet tall was always meant for drama, even in the days of its seclusion in a monastery in the Chartruese de Champmol. Claus Sluter's Well of Moses was an integral piece that influenced the Northern Renaissance's shift from stylized figures towards realistically, dramatically, and individually depicted figures in sculpture in the beginning of the 15th century Germany. This shift in depiction was vital to the expansion and assistance in modern devotion of this time. By portraying figures in such a manner, the stone becomes flesh and their life-like qualities have an affect on the viewer by assisting in reaching a mystical and intimate devotion by making their faith life real, present, and demanding of their attention.1 Sluter himself joined a monastery the same year that the Well of Moses was completed, which further connects the affect that the detailed emotions shown in the piece can create for a viewer.2

The figures depicted in the Well of Moses are Christ Jesus, and the Old Testament Prophets: Moses, David, Jeremiah, Zechariah, Daniel and Isaiah. Sluter displayed these life-size figures in a hexagonal manner so as to guide the viewer all the way around the sculpture to make eye contact with the figures on every side.3 Sluter chose this arrangement purposefully in order to move the viewer around the piece visually and direct the attention of the viewer towards their faith through the majestic and dominating presence of Christ and his prophets.4 The upper portion of the sculpture once contained a Calvary scene with Christ on the Cross, the Virgin Mary, St. John, and Mary Magdalene, but now only fragments of Christ’s torso remain. Sluter portrayed Christ in a way that viewers would look up into his face and experience empathy.

Today the drama is still felt but has perhaps lost some of the emotion that early 15th century viewers would have experienced from the presence of the Great Cross atop the fountain. The crucifixion scene was the focus back in the creation of the fountain, guiding viewers to feel empathy and repentance of their sins when looking to the Savior’s sacrificed body. If their gaze broke from the cross, their eyes were met with the life-size prophets pointing to inscriptions of their visions foretold. With these expressions of ferocity, animation, passion, and intimidation, viewers were surely assisted in having a spiritual experience. Today, the cross is no longer attached to the fountain but the forceful presence of the prophets remains.

The importance of each of the prophets can be explained by the way that they are sculpted and the inscriptions and symbols they carry. Researchers have discovered that the orientation of the Well was with Christ’s body facing East.5 With this information we find that David is directly beneath where the cross was originally placed. This careful positioning goes along with David being recognized as falling in lineage with Christ. Moses carries the Tables of the Law, or the Ten Commandments, the Law of God which was sent to Moses to share with the world, as well as displaying horns which were typical of medieval depictions to represent rays of light (Fig. 1).6 In Jesus’ life he preached the Tables of the Law in his Sermon on the Mount. By dying on the cross in fulfillment of the Old Law with a promise of a New Covenant was foretold by Jeremiah and accomplished by Christ. The figures all hold their prophecies and each have their heads turned in a manner that helps the viewer circulate around the fountain. Each of the prophets has an individualized face ripe with emotion shown through details on their faces by furrowed brows, fierce gazes, vulnerability, scruffy beards, and billowing garments, that despite their animation, fall naturally and realistically as though a living human body was beneath.

The drama of Sluter’s sculpture was inspired by the sacred theaters of the time.7 Because the general public did not have access to the Bible, liturgical dramas were common for telling the stories of the Bible and sharing moralities. The grand scale of the sculpture and costumes worn by Sluter’s prophets furthers this concept that his sculpture was a stagnant version of the religious theatricals of his day. Because of the plays, people were familiar with the prophets and the roles that they played making them easily recognizable. This is another link in how the drama inspired by the plays and instilled into the Well of Moses figures has influenced personal devotion in the 15th century.

Sluter himself must have been moved in his own faith through the creation of his sculpture because he joined a monastery towards the completion of the Well. The drama of these figures certainly assisted viewers in mystical visions and personal devotion because of the overwhelming power and emotion from the intense gaze of the prophets that evoke discipline, Christ's expression of pain that evokes empathy, and even from the angels wrought with grief for their crucified Lord as they wipe the tears from their eyes.8 The Well of Moses was able to convey the emotions of an oil painting by expanding the constrictions of a frame and making the figures come to life, setting the bar higher for the expections of 15th century German sculptures in their assistance in personal devotion.

Works Consulted

Freedberg, David. "Claus Sluter's Mourners." ARTNews 94, no. 1 (1995): 119-121.

Kuhn, Charles Louis. German and Netherlandish Sculpture, 1280-1800. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Pr., 1965.

Morand, Kathleen. Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

Müller, Theodor. Sculpture in the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Spain: 1400 to 1500;. Baltimore: Penguin, 1966.

Nash, Susie . "Claus Sluter's 'Well of Moses' for the Chartreuse de Champmol Reconsidered: Part 1." The Burlington Magazine 147 (2005): 798-809.

Endnotes

1 Freedberg, "Claus Sluter's Mourners." 119

2 Morand, Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy.

3 Nash, "Claus Sluter's 'Well of Moses' for the Chartreuse de Champmol Reconsidered: Part 1." 798

4 Müller, Sculpture in the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Spain: 1400 to 1500. 11

5 Morand, Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. 101

6 Morand, Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. 97

7 Morand, Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. 103

8 Freedberg, "Claus Sluter's Mourners." 119