The Drapery

Jessica Ott

Claus started a revolution in the art world thru the way he carved drapery, influencing 15th century artists such as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Matthias Grunewald, and Hans Multscher.1 Claus Sluter is most famous for his sculptures at Chartreuse de Champmol in Dijon. The first sculptures Sluter completed are the portal sculptures at Chartreuse de Champmol (Figure 1). The sculptures are of the Madonna and Child, St John, St. Catherine, and the Duke and Duchess of Burgundy.2

Claus started a revolution in the art world thru the way he carved drapery, influencing 15th century artists such as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Matthias Grunewald, and Hans Multscher.1 Claus Sluter is most famous for his sculptures at Chartreuse de Champmol in Dijon. The first sculptures Sluter completed are the portal sculptures at Chartreuse de Champmol (Figure 1). The sculptures are of the Madonna and Child, St John, St. Catherine, and the Duke and Duchess of Burgundy.2

Figure 1: Claus Sluter, Portal Sculptures, 1389-1406, Web Gallery of Art

The next project Sluter completed for the Chartreuse de Champmol was the Well of Moses (Figure 2). The Well of Moses was simply known as The Great Cross or Fons Vitae at the time due to the 14 ft. crucifix and fountain which has since been destroyed. Six prophets forming the hexagonal base for the destroyed cross survive today. The prophets are Moses, David, Jeremiah, Zechariah, Daniel, and Isaiah.3

Figure 2: Claus Sluter, Well of Moses, 1395-1406, Web Gallery of Art

Sluter’s final project for the Chartreuse de Champmol was The Tomb of Philip the Bold (Figure 3). In this sculpture 41 pleurants or mourners march around the tomb in a funeral procession.4 All of these sculptures are united by Sluter’s use of dramatic drapery.

Figure 3: Claus Sluter, Tomb of Philip the Bold, 1390-, Web Gallery of Art

The drapery in Claus Sluter’s sculptures is truly innovative and creative in thinking. When compared to Andre Beauneveu, a sculptor working during the same time period as Claus Sluter, Sluter’s creativity is apparent. Beauneveu uses stylized drapery in his sculptures, such as his Prophet A (Figure 4). Beauneveu employs sweeping curves, graceful flowing fabric, and a weightless body covered by a piece of fluid fabric. Even the curve of the body and the waves of the beard are portrayed in such a way to emphasize how smooth and graceful this figure is.5 Claus Sluter’s drapery by contrast, shows that there is definite weight beneath. His drapery is dense and voluminous.6 Where Beauneveu’s sculpture is graceful and stylized, Sluter’s sculptures shout of a physical presence in a dramatic scene. Sluter is partially able to achieve this drama and presence through the use of undercutting.7 Undercutting is cutting away from the stone to leave a portion of the stone overhanging. Undercutting allowed Sluter to show movement and energy where before artists showed elegant and polished figures. Sluter’s Virgin and Child from the portal highlight the ways in which he utilized drapery to move the viewer’s eye to the focal point of the sculpture.8 All of the folds and gathers point directly to the baby Jesus in Mary’s arms. The ample cloth gathered at the Virgin’s arms does not conceal the fact that she has weighty, human arms; it accentuates it. Even baby Jesus’ garments show his physical weight, making him much more human than Beauneveu’s sculptures. Sluter also possesses the ability to make drapery assume human emotions. On The Tomb of Philip the Bold several of the pleurants faces are not shown, and yet the viewer can sense the emotional state of the mourner purely by the drapes and folds of fabric, and the stature of the person.9 While the pleurants are small in size, they seem large to the viewer due to their dynamic presence and intense emotions.10 Sluter uses drapery to accentuate the humanoid aspects of his sculptures, while also making them seem other-worldly with their powerful presence in space.

Figure 4: Andre Beauneveu, Prophet A, Late 14th Century, Gesta

The trend that Claus Sluter started with his drapery is that of naturalism and realism. Many artists who followed Sluter adopted this style.11 Sluter does not adhere strictly to realism, but instead manipulates a realistic setting and elements for the upmost impact. Drapery folds and gathers do exist in clothing, but not to the extent in which Sluter portrayed them.12 He used and modified the drapery to convey his message in the best possible way; just as 15th century artists did in elements of their paintings. In Jan Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, van Eyck employs the use of dramatic drapery to emphasize his heavenly court’s human weightiness(Figure 5). Though the figures are clearly enthroned in the otherworldly; they are firmly grounded in this world through van Eyck’s modification of drapery and other elements. The frames and multiple viewpoints are another tool Jan van Eyck used to distinguish the heavenly from the earthly.13 These elements also help the viewer more easily transcend into the other-worldly, as does Claus Sluter’s use of drapery. The way Sluter carved the drapery looks like realistic clothing, but it also gives his figures a lifelike dynamic quality that makes them relatable. These aspects are so powerful and dramatic they are untouchable to the viewer.

Figure 5: Jan van Eyck, Ghent Altarpiece, 1432, Web Gallery of Art

This combination of contradictions was one that later artists strove to create in their own work. Rogier van der Weyden’s Deposition conveys emotions that are relatable and real; much like Claus Sluter’s pleurants in The Tomb of Philip the Bold(Figure 6). Rogier van der Weyden utilizes dramatic drapery, and facial expressions to convey emotion. Sluter also employs dramatic drapery in his pleurants to illustrate extreme grief. While the emotions are something the viewer can clearly relate to, the presence and dramatic power illustrated in both pieces clearly separates the human and the godly.

Figure 6: Rogier van der Weyden, Deposition, 1435, Web Gallery of Art

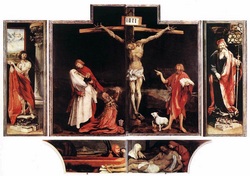

Matthias Grunewald’s gory Isenheim Altarpiece utilizes drapery, human emotions, and a dramatic presence much in the same way(Figure 7). When viewing the Isenheim Altarpiece the viewer can feel Christ’s pain, feel the emotions Mary is feeling, and yet they cannot truly be embedded into the scene due to the vast and untouchable presence that the piece has.

Figure 7: Matthias Grunewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, 1515, Web Gallery of Art

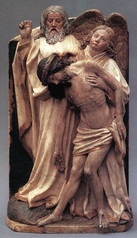

Hans Multscher is a renaissance artist whose style is influenced by Claus Sluter. Multscher mimics Sluter’s style of drapery in his sculptures. In his Holy Trinity he uses drapery to cover the Trinity, and to show that they have realistic weight and bodies(Figure 8). Multscher also uses intense emotions to connect with the viewer, much as Sluter did. Multscher relies more on facial expressions and stance, whereas Sluter used fabric and humanism as his backdrop for the viewer’s awe and empathy. While none of these artists directly copied Claus Sluter’s work, they were all influenced by the majesty of his work, and strove to recreate that impression in their own work.

Figure 8: Hans Multscher, The Holy Trinity, 1430, Web Gallery of Art

Claus Sluter using drapery on his figures might not seem like a pivotal moment in art history, but he used drapery to emphasize, highlight, and elevate his sculptures to new places. Places the viewer could only hope to enter; yet Claus Sluter restrains from making his sculptures unobtainable by making them entirely lifelike with human emotions and energy coursing over their every surface. An art revolution followed with many others hoping to obtain this same glorious contradiction.

Bibliographies

Morand, Kathleen, Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

Snyder, James, Northern Renaissance Art: Painting, Sculpture, the Graphic Arts from 1350-1575. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1985.

Moffitt, John F. “Sluter’s “Pleurants” and Timanthes’”Tristia Velata”:Evolution of, and Sources for a Humanist Topos of Mourning.” Artibus et Historia 26 iiinnnnnni(2005): 73-84.

Scher, Stephen K. “André Beauneveu and Claus Sluter.” Gesta 7 (1968): 3-14.

Harbison, Craig. “Visions and meditations in Early Flemish Painting.” Simiolus 15(1985): 87-118.

Morand, Kathleen, Claus Sluter: Artist at the Court of Burgundy. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

Snyder, James, Northern Renaissance Art: Painting, Sculpture, the Graphic Arts from 1350-1575. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1985.

Moffitt, John F. “Sluter’s “Pleurants” and Timanthes’”Tristia Velata”:Evolution of, and Sources for a Humanist Topos of Mourning.” Artibus et Historia 26 iiinnnnnni(2005): 73-84.

Scher, Stephen K. “André Beauneveu and Claus Sluter.” Gesta 7 (1968): 3-14.

Harbison, Craig. “Visions and meditations in Early Flemish Painting.” Simiolus 15(1985): 87-118.

Endnotes

1.) Morand, 110.

2.) Morand, 79-83.

3.) Morand, 91-101.

4.) Morand, 121-131

5.) Scher, 9-11.

6.) Snyder, 66.

7.) Morand, 82.

8.) Synder, 65

9.) Moffitt, 77.

10.) Moffitt, 76.

11.) Scher, 11.

12.) Morand, 131.

13.) Harbison, 107-108.

1.) Morand, 110.

2.) Morand, 79-83.

3.) Morand, 91-101.

4.) Morand, 121-131

5.) Scher, 9-11.

6.) Snyder, 66.

7.) Morand, 82.

8.) Synder, 65

9.) Moffitt, 77.

10.) Moffitt, 76.

11.) Scher, 11.

12.) Morand, 131.

13.) Harbison, 107-108.